Event Highlights: Compensation for a Just Energy Transition in International Investment Law and Domestic Law

Martin Dietrich Brauch, Ella Merrill, and Jack Arnold

May 19, 2022

Also vailable in PDF here.

Key Messages

- International and domestic legal frameworks can shape equitable outcomes to the climate crisis by determining how costs and benefits are distributed. Existing frameworks create privileges for fossil fuel asset owners, allowing them to receive massive compensation from states.

- Domestic legal frameworks on compensation should focus primarily on the needs of disproportionately affected populations, while international legal frameworks should ensure that all states have adequate resources to invest in climate mitigation and adaptation, and cover the growing costs of loss and damage. A state-led decision-making forum should define principles and criteria on compensation.

- Any compensation that a fossil fuel company might receive should be conditioned upon the prohibition of reinvesting it in fossil fuel projects and related infrastructure, and upon enforceable just transition obligations imposed on the company for the benefit of its employees.

- International investment law is largely driven by investment treaties and their interpretation by arbitral tribunals, granting foreign investors and investments extraordinary protections through clauses such as expropriation, most-favored nation (MFN) treatment, national treatment, and fair and equitable treatment (FET).

- The concept of “legitimate expectations” in investment treaties has been interpreted as requiring host states to provide stability to investors, thus insulating investments from regulatory or fiscal change. The expectation that host states be required to provide regulatory stability lacks basis and should be rejected. Fossil fuel investors should not receive any compensation when assets are stranded as a result of government policies.

- Several instances of regulatory chill have resulted from real or anticipated investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) claims from fossil fuel investors. Where governments do follow through with policies, they may end up paying exorbitantly high compensation to fossil fuel investors from public coffers.

- Tribunals usually apply the customary standard of full reparation in calculating compensation, aiming to re-establish, as far as is possible, the situation that would have existed had the unlawful act not been committed.

- Compensation rules in international investment law must be reformed; at the very least, there should be hard caps placed on compensation. Treaty termination is the best way to avoid liability for climate-related claims.

- Investment treaties have thus far not meaningfully mentioned climate implications. The treaties’ silence on these issues leaves significant room for tribunals to follow claimants' suggestions on how to account for it.

- The main question for tribunals remains: Who will bear the cost of decarbonization? Will it be investors, who receive lower compensation for lost assets, or states, through the mandate to provide higher compensations to investors that do not account for climate risks in assessing the damages?

- To achieve the zero-carbon transition, governments and development banks should develop appropriate and accurate mechanisms to rapidly close down heavily polluting fossil fuel assets on a global scale while preventing unfair, inequitable, and overestimated compensation for those who have profited from the climate crisis.

- Germany’s overcompensation to lignite power plant owners serves as an important lesson for governments on avoiding mistakes that lead to the overcalculation of compensation. To facilitate the energy transition, governments should design legislation to avoid compensation cases with fossil fuel asset owners.

The Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (CCSI) and the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law co-hosted a webinar focusing on legal approaches to compensation for a just energy transition.

The event was moderated by Michael Burger, Executive Director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. Achieving the goal set by the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels will require incredible efforts on the part of states to rapidly shift away from fossil fuels and decarbonize the global energy system. The role played by international and domestic legal frameworks will of course play a significant role in these efforts. The event placed a special focus on international investment law, and its approach to investor compensation, for achieving a just energy transition that considers the distributional equity impacts on all stakeholders. The following sections summarize panelists' interventions.

Martin Dietrich Brauch: The Importance of Considering Equity in a Climate Change and Energy Transition Context

Martin Dietrich Brauch, Senior Legal and Economics Researcher at CCSI, set the stage for the event, outlining the importance of considering equity—including frameworks such as climate justice and just transition—in the context of climate change and the energy transition, and kickstarted the discussion on how much, if at all, fossil fuel companies should be compensated for shutting down their operations in order to meet the energy transition goals set forth in the Paris Agreement.

Brauch noted that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2022 report on climate mitigation emphasizes that “ambitious mitigation pathways imply large and sometimes disruptive changes in economic structure with significant distributional consequences within and between countries.” Within countries, he elaborated, activities will need to be shifted from high-emission activities to low-emission activities, and warned that jobs in high-emission industries will need to be replaced with new, low-emission jobs in the zero-carbon economy.

Countries will also feel disparate impacts of climate change and of the energy transition, thus making it critical for them to consider the impact of upcoming transitions on various communities around the world. Countries with economies that are currently particularly dependent on fossil fuels, and those who are particularly vulnerable to the physical impacts of climate change, are those most exposed to negative economic and fiscal implications over the coming decades.

International and domestic legal frameworks play a key role in shaping equitable outcomes by determining how costs and benefits are distributed. Existing frameworks create privileges for fossil fuel asset owners, allowing them to receive massive compensation from states. While fossil fuel companies do bear transition risks and costs, their exposure does not translate into vulnerability. These companies have long known about their contributions to climate change, and have substantial economic power that protects them from heightened levels of risk and uninsured costs.

When considering who should receive compensation to adapt to and mitigate climate change, Brauch urges to consider the following questions regarding the distribution of costs and benefits:

- Who is more vulnerable to suffering the risks and bearing the costs of climate change and the energy transition?

- Who can afford to bear those costs?

- Who should pay compensation?

- Who should benefit from compensation?

Brauch suggested that domestic legal frameworks look inward to focus primarily on disproportionately affected workers and communities. International legal frameworks, conversely, should ensure that all states have adequate resources to invest in climate mitigation and adaptation, and cover the growing costs of loss and damage. They should also ensure that compensation is available for low-income countries that are vulnerable to climate and transition impacts and have the least accessibility to public finance.

When it comes to the compensation of fossil fuel companies, Brauch emphasized that any compensation that a fossil fuel company might receive must be conditioned upon the explicit prohibition of reinvesting any compensation received in fossil fuel projects and related infrastructure, and upon enforceable just transition obligations imposed on the company for the benefit of its employees.

Rather than putting private arbitrators in the driver’s seat on issues of valuation of fossil fuel assets and compensation, states should bring these discussions to a state-led decision-making forum that would define principles and criteria on compensation, including procedural justice mechanisms to ensure that input from those affected is taken into account, their rights are realized, and their needs are met.

Kyla Tienhaara: ISDS: Raising the Cost of Climate Action

Kyla Tienhaara, Canada Research Chair in Economy and Environment at the School of Environmental Studies and the Department of Global Development Studies at Queen’s University, presented on the valuation of damages in international investment law. She framed her intervention by posing three questions:

- Should fossil fuel investors receive any compensation when assets are stranded as a result of government policies?

- If there are circumstances in which fossil fuel investors should receive compensation, who should decide the amount?

- Do the compensation rules in international investment law need to be reformed?

There are over 2,600 bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and treaties with investment provisions in force. Investment treaties can protect foreign investors and investments from direct and indirect expropriation by host states, and provide additional protections through most-favored nation (MFN) and national treatment clauses (non-discrimination clauses), and fair and equitable treatment (FET) clauses. This last type of clause may be the most problematic, as it has been interpreted as requiring host states to provide stability to investors, thus insulating investments from regulatory or fiscal change.

The argument that host states have committed to provide regulatory stability lacks basis and should be rejected. In the case of climate-related disputes, international agreements on climate date back to 1992, with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and the existence of these agreements should have been sufficient warning to fossil fuel investors that governments would have to act to curtail production. Furthermore, the lack of government action to date is a direct result of policy obstruction and lobbying by fossil fuel firms.

Investment protections are enforceable through investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). ISDS cases are decided by private tribunals with three party-selected arbitrators. This CCSI Primer on ISDS is a helpful source for those looking to learn more about it.

The intervention addressed five key climate-related ISDS cases—three were based on the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), the other two on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The cases were Rockhopper v. Italy, RWE v. Netherlands, Uniper v. Netherlands, Westmoreland v. Canada, and TC Energy v. United States.

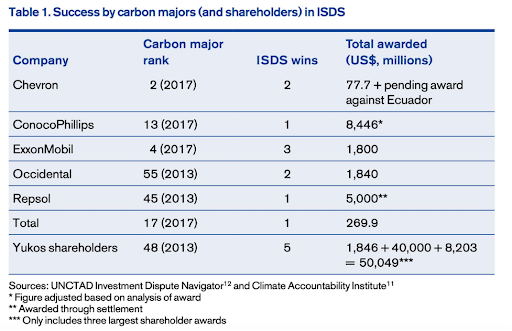

The table above (from Tienhaara and Cotula 2020) demonstrates the amount of public funds that have been flowing to carbon majors through ISDS awards. Because of the size of potential awards, the mere threat of an investor claim is enough to dissuade governments from taking climate action. Several instances of regulatory chill have already resulted from real or anticipated claims from fossil fuel investors. In 2017, the French Minister of the Environment drafted a law that would end fossil fuel extraction on French territory before 2040. Vermilion, an oil and gas company, threatened to sue France through the Energy Charter Treaty. The Ministry subsequently weakened the legislation, and the case was dropped. In 2022, it was reported that both New Zealand and Denmark had designed their plans to phase-out oil and gas production in ways that would avoid ISDS claims.

In the cases where governments do follow through with policies, they may end up paying more compensation than they otherwise would have. We have examples of this from the global North (e.g., German coal phase-out), but the implications are much graver for the global South.

The following conclusions were reached with regard to the questions posed at the beginning of the intervention:

- Should fossil fuel investors receive any compensation when assets are stranded as a result of government policies? No, because there should be no expectation of policy stability, and fossil fuel investors have actively created their own expectations that action will not be taken. However, a government may decide that it is politically expedient to compensate in some circumstances.

- If there are circumstances in which fossil fuel investors should receive compensation, who should decide the amount? A democratically elected government. However, if investors have access to ISDS, they will be able to use the threat of arbitration to try to influence the amount of compensation governments offer.

- Do the compensation rules in international investment law need to be reformed? Yes. Termination of investment treaties is preferable, but at the very least, there should be strict caps on compensation—either limiting it to sunk costs or considering more sophisticated proposals that take into account whether the state benefited from the action that breached the treaty.

Blanca Gómez de la Torre: Overview of Valuation of Damages Approaches used by ISDS Tribunals

Blanca Gómez de la Torre, Partner and Head of Dispute Resolution at ECIJA GPA, and former National Director for International Affairs and Arbitration at the Ecuadorian Office of the Attorney, picked up the conversation to cover the issue of valuation of damages in concluded ISDS cases. Monetary compensation is the only remedy in ISDS. There are several approaches to calculating damages.

Treaties require monetary compensation for lawful expropriations. To calculate damages, most treaties require tribunals to use the fair market value of the expropriated investment, as of the date prior to the taking. In some cases, treaties have applied this standard to unlawful expropriation as well. TecMed v. Mexico is an example.

Tribunals usually apply the customary standard of full reparation, for example in Burlington v. Ecuador and Crystallex v. Venezuela. This means that reparations must, to the extent that is possible, re-establish the situation that would have existed were the unlawful act not committed. Reparations usually cover fair market value, increase of value from date of taking all the way up to the award, and any consequential damages, such as loss of opportunity costs. For example, in Perenco v. Ecuador, the tribunal awarded $25 million for the loss of opportunity, meaning the opportunity to extend an oil block.

To calculate the fair market value of a loss, there are three approaches. Tribunals have the discretion to choose which methodology will be used in any given case. The approach used to value damages can significantly impact the outcome of a case. In Murphy v. Ecuador, the tribunal indicated that the choice of the valuation methodology has a significant impact on the final damages calculation.

The three main approaches used by tribunals to calculate damages are:

- The income-based approach: The most commonly used approach. This includes the discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis.

- The market-based approach: This uses stock market comparison to calculate damages.

- The asset-based approach: A far less used approach compared to the other two. It entails looking closely at the investor’s books and real investments. According to most tribunal findings, this approach sets an account for the true value shareholders could extract from the investment and accounts for any specific risks to the investment. It does not require forecasting and speculative discounting but fails to correctly account for the true value shareholders can extract.

In the case of oil concessions, the following criteria is considered: number of barrels of oil produced, the price of oil, and the value, quality, and size of the deposits. In Occidental v. Ecuador, reserves were estimated. It is standard practice to adjust these numbers based on their category in order to estimate future production. These estimations are used by the company itself for reporting purposes. The second criteria used is the company’s future and historic production capacity and sales. The third is a data-based estimation of future oil prices. In Burlington v. Ecuador, the tribunal used a long-term forecast, while in Phillips v. Venezuela, the tribunal used the forecast over a shorter time period, and adjusted prices for inflation beyond a short-term horizon. The fixed-term nature of contracts is another criteria that can be used to determine the value. For example, the tribunal in Burlington v. Ecuador used the contract end-date as the temporal limit to its calculation.

Climate implications have thus far not been meaningfully mentioned in investment treaties. But the treaties’ silence on these issues leaves significant room for tribunals to hear claimants' suggestions on how to account for it.

Tribunals are neither the right nor wrong venue for settling these issues. But, in reality, they have already become the venue, and so now, the question is: who is going to endure the cost of decarbonization—Will it be investors, who receive lower compensation for lost assets, or states, through the mandate to provide higher compensations to investors that do not account for climate risks in assessing the damages? In the case of the Inter-American Development Bank, the burden of decarbonization has been placed on the state; on the other hand, companies in the energy industry have received pressure from policymakers and activists to take their own actions to address climate change.

Dave Jones: Case Study on Germany’s Flawed Lignite Compensation

Dave Jones, Global Programme Lead at Ember, presented an analysis of Germany’s flawed compensation scheme for owners of lignite power plant owners, which consequently caused the German government to massively over-compensate such owners.

Greenpeace Germany, through a freedom of information request to the German government, received the formula, and thereby the assumptions, that Germany used to compensate two owners of lignite power plants €4.4 billion for the closure of their heavily-polluting assets. The compensation package had three flaws in its underlying assumptions, resulting in the payment being unfair and overly generous.

The deal itself was a bilateral deal between each of the lignite companies—RWE and LEAG—on one side and the German government on the other, and therefore was not a deal in the international context. The flawed assumptions in this case included the following:

- When the government assessed the compensation for the lignite plants, it looked at market prices of forward power and carbon prices between 2017 and 2019, which led to the valuation of €4.4 billion. Had the government used market prices for 2020, however, the valuation would have been reduced by nearly half, to €2.56 billion. Thus, the time period that is used for the valuation of an asset is critical in determining its valuation.

- In its model, the government only included variable costs, and omitted fixed costs altogether. Had the government included fixed costs in the calculations, particularly because many fixed costs related to the plant and mining activities are unavoidable, the compensation amount would have dropped substantially.

- The duration of the payment also plays a crucial role in the final valuation of compensation. The longer the payment duration, the higher the total amount. The German government decided to use a 4- to 5-year payment schedule in its model, despite the companies’ plans to end their use of the relevant plants prior to the final deadline of the payment plans.

Future compensation cases for fossil fuel assets, in particular coal power plants, are likely to look to this case for guidance. Thus, understanding the flawed assumptions made by the government in this case and learning from them will be crucial to avoid inequitable compensation in future cases.

To reach the goals set out by the Paris Agreement, it is vital that governments and development banks develop appropriate and accurate mechanisms to rapidly close down heavily polluting fossil fuel assets on a global scale while preventing unfair, inequitable, and overestimated compensation for those who have profited from the climate crisis.

Above all, governments need to design legislation that does not open them up to compensation cases. Fossil fuel companies fighting compensation cases is a massive and avoidable distraction that is already visibly slowing the transition.

Investor claims are likely to lead to regulatory chill, overcompensation, or both, and thus to the diversion of resources needed to enable a necessary and urgent technological shift and to compensate workers and communities affected by climate change and the energy transition. Even between economists, the choice of a discount rate in valuation methods is a complex issue that becomes an ethical and equity question—how do we value future generations? Rather than trying to sort this out, why not impose the discount rate that is most desirable for appropriate valuation from an ethical perspective?

The solution to these issues is not going to arise from the decision of investment tribunals. Even if countries attempt to reform treaties to incorporate a discount rate that accounts for decarbonization, the reality is that it would still be impossible to predict how tribunals would decide. Governments could also take steps to include a higher, nationally recognized carbon price, thus implicating themselves in the negotiations on valuation, but these measures, which are outside of the spheres of international investment law, may not suffice to prevent arbitration claims.

Given that interpretations by investment tribunals may ultimately frustrate any attempts at piecemeal reform of the regime, and that the regime's existence itself continues to allow threats of regulatory chill and overcompensation that hinder climate action, terminating or withdrawing from treaties or withdrawing consent to ISDS are more effective reform options.

CCSI on International Investment Law and a Just Energy Transition

This April 14, 2022 webinar was part of CCSI’s work to understand the underlying issues and design policies to improve international economic governance for climate mitigation and adaptation in line with achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

Our portfolio on investment and trade law and climate policy includes our research on international investment agreements from climate policy and environmental and climate justice lenses, on the need to move away from climate-blind investment protection and arbitration treaties toward investment governance treaties, and on the Energy Charter Treaty more specifically. CCSI has also produced research and writing on the issue of valuation and damages in ISDS. Much of our work in this area comes from our three-pillar framework for designing international investment agreements in line with the SDGs.

Visit our Climate Change page, subscribe to our mailing list, or contact the authors directly to learn more about these and other CCSI activities in this field.

Martin Dietrich Brauch is Senior Legal and Economics Researcher at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (CCSI). Ella Merril and Jack Arnold are Program Associates at CCSI.