Political Will: What It Is, Why It Matters for Extractives and How on Earth Do You Find It?

Executive Session on the Politics of Extractive Industries

As the Executive Session explores the ways in which political realities impact reforms in the extractive industries, the conceptual and practical shortcomings of “political will” as the traditional starting point become increasingly apparent. Executive Session participant, scholar at the University of Birmingham and advisor to UK DFID, Heather Marquette, weighs in on this issue and the importance of extractives governance practitioners unpacking the concept in order to more effectively understand and engage with political issues in their work.

An experienced development policymaker once said to me, ‘My kids know that “lack of political will” and “Coldplay” are two things that I don’t want ever to hear in our house’. His frustration is born out of years of hearing excuses for why development interventions didn’t deliver anticipated outcomes: ‘It’s not my approach that was the problem; it’s the lack of political will’. Lurking in this apparent absence is a very real presence – too much ‘active political won’t’ and too few attempts to overcome this.

Almost ten years ago, Oxfam’s Duncan Green wrote about his frustration with the term, calling it ‘lazy and unproductive’. He compared it to the way people used to talk about ‘good governance’, as if it’s a ‘magic wand that will guarantee implementation – no power, no politics, just good governance. Words that fill a vacuum where political analysis should be’.

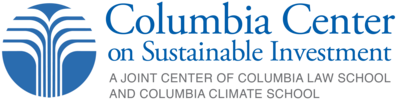

It is, of course, vital to understand whether or not there is political will to carry out much needed reforms. Reforms simply don’t happen without political will. . But political will has become a global shorthand for explaining why reforms succeed or fail, as any cursory look at the news or Twitter can tell you. But – as colleagues of mine and I argue – this leaves political will as an almost useless ‘black box’ – ‘a system or object that changes outcomes: things come out differently to how they go in. At the same time, its inner workings − what’s really going on inside − are opaque…If we don’t understand it, we can’t re-create it.’ Political will may be a useful descriptive label, but it doesn’t tell you enough about what is actually going on or anything about what actually needs to happen. Thinking about political will as a general sort of challenge is different to understanding this challenge in a more operationally useful way, a way that helps us understand what to actually do about it.

Derrick Brinkerhoff has defined political will as ‘the commitment of actors to undertake actions to achieve a set of objectives…and to sustain the costs of those actions over time’. In few sectors is the need for political will – the sustained commitment towards developmental objectives – more important than in extractives. It’s estimated that 3.5 billion people live in countries with oil, gas and minerals, and EITI report $3.2 trillion in revenues have been disclosed through their reports. While extractives industries – and the tax revenues they raise – can make important contributions to a nation’s growth, employment and development, they’ve also been linked to negative health impacts, illicit financial flows, serious and organised crime, environmental disaster, conflict, sex trafficking and even assassinations.

Recently, the World Bank called out for an approach to transparency in the extractives sector to help create conditions that better work for resource rich host communities. They explain: ‘If sufficient political will exists to meet public commitments to disclose critical information, the regulatory systems that legitimise and conceal corruption and impede accountability will begin to crumble’.

Writing about Afghanistan’s massive extractives wealth, Global Witness warn of the potential for extractives to lead to the dreaded ‘resource curse’ rather than developmental progress. Only if the Afghan government and international donors ‘muster the political will’ to enforce strong protective policies will this fate be avoided.

Work by Chatham House researchers on the so-called ‘resource curse’ sums up why political will is such a problematic concept and why it is a ‘black box’. Writing about the relationship between extractives and economic development, they say:

Achieving institutional good governance in countries with a relatively low capacity to manage the extractive sector at the outset will be a long, hard slog right from the very beginning. It will require both sustained political will and a measure of societal stability. At the same time, while it is known what needs to be done for extractives-led development to have a positive outcome, the reality of the political economy that develops around an extractive industry or other, similar forms of rent- generating activity, may make it impossible to achieve that outcome.

So far, so descriptive at best, fatalistic at worst. All of these quotes tell us (convincingly) that political will is vital. None tell you how to get from A to B.

In its 2018 progress report, EITI notes that while increased transparency may be partly attributed to its work, other factors – including political will – also impact on countries’ progress. But it continues to treat political will as an exogenous factor, rather than a political process of which EITI is part. Political will is the black box into which lots of things continue to be thrown, but we don’t know what happens to them while they’re in there until they come out as either success or failure.

In our synthesis of ten years of research by the Developmental Leadership Program, we’ve had a go at trying to unpack this black box. Getting into this box and answering some of the questions here, among others, is an important first step in figuring out how to move powerful actors in the sector from ‘political won’t’ to ‘political will’. This involves identifying motivated actors who are able to work in cooperation with others in order to overcome barriers in a way that is seen as legitimate by various stakeholders, and then supporting them. This is mirrored in DFID-funded research on anticorruption in the Nigerian extractives sector, on convincing high net worth individuals in Uganda to pay their taxes, on encouraging important local content reforms in Ghana, and so on. As the research shows, reforms that find ways to tap into the actual incentives of businesses and individuals tend to be more political viable and, hopefully, more sustainable.

This involves taking risks, because these actors aren’t magic bullets in themselves. Sometimes interventions succeed and sometimes they don’t, as our research on the FOSTER programme in Nigeria has shown. ‘Thinking and working politically’ – drawing on strong political analysis, working closely with local (and legitimate) actors, being flexible and adapting to changes in the political landscape – can help reduce these risks and overcome barriers. And sometimes ‘political won’t’ is a legitimate response to challenging contexts that can’t, and perhaps shouldn’t, be shifted. Only sound political analysis can tell you if this is the case.

Sometimes political will simply isn’t enough, if other technical aspects are wrong too. In this sense, political will can be a necessary, but not sufficient, factor in extractives reform success. As DFID colleagues and I have argued, sometimes approaches ‘focus exclusively on political aspects and underplay (or ignore) the technical challenges that remain to both government and donor programmes. Everything is simultaneously technical and political. [We need to look] through both “technical” and “political” lenses to understand inefficiencies, institutions and incentives as well as ideas, norms, values, networks and behaviours’.

The challenge for actors interested in reforms in the extractives sector is to dive into the political will box and find out what’s happening there and – importantly – what is politically and technically possible and what isn’t. It isn’t an easy path, but it’s likely to be the only path to successful reform.